Meet Pillar Security at RSA 2026

Meet Pillar Security at RSA 2026

Learn more

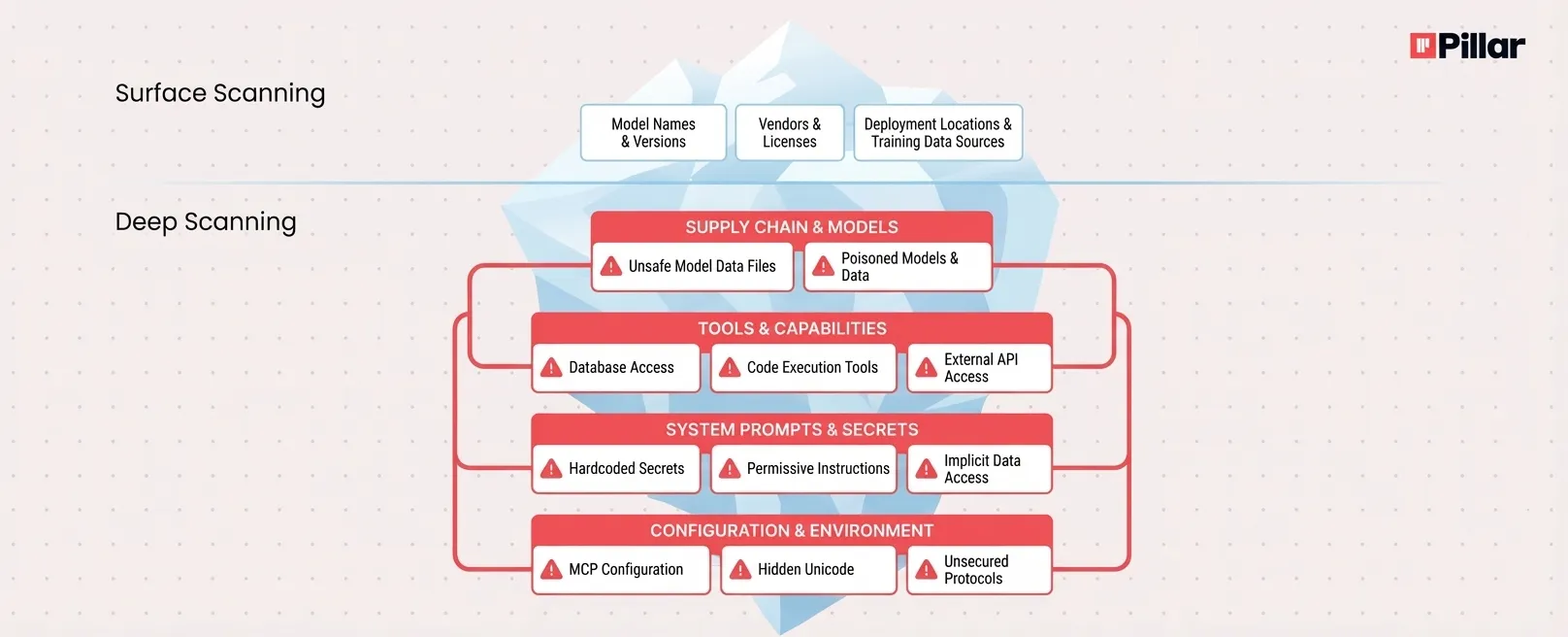

Security teams face growing pressure to inventory AI applications, but listing models and vendors reveals almost nothing about actual risk. The blast radius of a prompt injection attack depends on what the AI controls: its tools, data access, and system instructions. The ability to protect AI assets is also a direct result of how well the security team understands the business goals of an AI application, its capabilities and its vulnerabilities. Deep repository scanning exposes these hidden layers, from pickle-serialized model files that can execute arbitrary code to configuration backdoors in AI coding assistants, to malicious data in RAG or training and many many more. Inventory satisfies compliance. Scanning the internals, paired with runtime guardrails, delivers security.

As organizations rush to build governance around Generative AI, the "AI BOM" (Bill of Materials) has emerged as a standard compliance artifact. The logic mirrors traditional AppSec: if you can list every library in your code, you can manage your risk.

Security teams are asking reasonable questions. Which models are we using? Are we calling OpenAI or hosting Llama locally? Do we have shadow AI applications running without oversight?

But answering those questions only solves the surface problem. Knowing which models exist tells you almost nothing about what they can do when compromised or how they can be compromised. That gap between inventory and insight is where real breaches happen.

Compliance frameworks love lists. Regulators want to know what AI systems you operate, how they were trained, and who maintains them. The EU AI Act, ISO 42001, and NIST's AI Risk Management Framework all emphasize documentation and traceability.

None of that is wrong. But documentation is a governance artifact, not a security control.

Consider what an AI BOM typically captures: model names, versions, vendors, training data sources, and deployment locations. Useful for audits. Useless for understanding what happens when an attacker lands a successful prompt injection.

The impact of that injection depends entirely on context. A compromised chatbot might generate an embarrassing response. The same attack against an agent with database access can lead to data exfiltration, privilege escalation, or persistent corruption.

Simon Willison, who coined the term "prompt injection," recently described what he calls the "lethal trifecta" for AI agents: access to private data, exposure to untrusted content, and the ability to communicate externally. When all three converge, attackers can trick the system into accessing sensitive information and sending it wherever they want.

Your inventory won't tell you which applications have that combination. Deep scanning will.

Surface discovery looks for API keys and model endpoints. Deep scanning looks at the artifacts, the configuration files (including MCP configurations and external sources), and the architectural patterns that define what an AI application can actually do, and what it relies on.

The difference matters because AI risk lives in layers that a simple inventory never touches.

Developers routinely pull pre-trained models from public hubs like Hugging Face. The ecosystem hosts over 200,000 PyTorch models, and the convenience is undeniable. But convenience comes with a catch.

Most of those models use Python's pickle serialization format. Pickle files can embed and execute arbitrary code during deserialization. An attacker who uploads a poisoned model to a public repository can achieve code execution the moment someone loads it.

Recent research makes the risk concrete. In 2025, security researchers disclosed multiple vulnerabilities in PickleScan, the tool Hugging Face and others use to detect malicious pickle files. CVE-2025-1716 showed how attackers could bypass static analysis entirely by calling pip.main() during deserialization. CVE-2025-10155 through CVE-2025-10157 demonstrated file extension tricks and CRC manipulation that caused scanners to fail while PyTorch loaded the malicious payload normally.

Your inventory might note "Llama 3, fine-tuned variant, pulled from Hugging Face." It won't tell you whether that model file contains a reverse shell that triggers on startup.

Modern AI frameworks like LangChain, Semantic Kernel, and AutoGen define "tools" as functions the AI can call. These tools bridge the probabilistic model and your deterministic infrastructure. They're what give agents the ability to query databases, execute code, send emails, or interact with external APIs.

Tools transform risk categories. Without them, prompt injection is a "read" vulnerability. With them, it becomes "write", “persist” and "execute."

An internal data analyst agent with an execute_sql_query tool can answer business questions. It can also DROP TABLE users if an attacker (or a careless internal user) crafts the right prompt. An agent with a run_python_code tool grants the LLM the same privileges as your application server.

Inventory captures "AI-powered data analyst, deployed Q2." Scanning the repository reveals the tool definitions, their scoping (or lack of it), and the blast radius of a successful attack.

The system prompt is the AI's operating manual: instructions that define its behavior, tone, constraints, and context. It acts as the "source code" of the AI's personality.

Another common issue, that is much harder to recognise but has incredible impact is permissive access to data, systems or capabilities. The inventory BOM says "customer support chatbot." Scanning the system prompt reveals implicit permission to access transaction history, a hardcoded refund authorization token, and no input validation between user messages and system instructions.

Identifying which frameworks orchestrate the AI matters because different frameworks carry different risk profiles.

LangChain, AutoGen, CrewAI, and LlamaIndex are designed for autonomy. They default to "loop until solved" behaviors, passing outputs between agents, retrying failed operations, and taking actions without human approval at each step.

Agents carry elevated risk around resource consumption, unintended loops, and cascading errors. A hallucination in one step can propagate through the entire workflow before a human sees the output.

Inventory records "internal productivity tool, uses OpenAI API." Scanning the codebase reveals LangGraph orchestration, multi-agent handoffs, and no circuit breakers on autonomous loops.

The newest attack surface involves the configuration files for AI coding assistants like GitHub Copilot, Cursor, and Windsurf, along with protocols like local MCP (Model Context Protocol) configs.

In March 2025, researchers disclosed the "Rules File Backdoor" vulnerability affecting both Copilot and Cursor. Attackers can embed invisible Unicode characters (zero-width joiners, bidirectional text markers) into configuration files that appear benign to human reviewers but contain malicious instructions for the AI. When a developer opens the project, their assistant reads those hidden instructions and can silently insert backdoors, introduce vulnerabilities, or exfiltrate data.

MCP configurations add another layer. These files define which external tools and servers the AI can access. CVE-2025-54135 and CVE-2025-54136 demonstrated how attackers could modify trusted MCP configurations after initial approval, achieving persistent code execution every time the developer opened their project.

A 2024 GitHub survey found that 97% of enterprise developers use GenAI coding tools. That's 97% of your development workforce potentially exposed to configuration-based attacks that inventory will never detect.

Deep repository scanning gives you the map. It reveals tools, prompts, frameworks, supply chain artifacts, and configuration risks. But AI applications require one last line of defense, so that even if they are perfectly configured malicious input simply won’t reach them..

Runtime guardrails close that gap.

Guardrails operate as independent, in-path security layers that validate inputs and outputs in real time. They enforce the policies that scanning reveals are necessary. If scanning shows an agent has database write access, guardrails can block SQL commands that match destructive patterns, or even block all code or requests from code snippets from user space. If scanning reveals a system with access to PII or credentials, guardrails can detect and redact data exfiltration attempts.

The relationship is complementary. Scanning without runtime leaves the application exposed to recon, analysis and malicious attempts.. Runtime without understanding the internals of your AI system leaves you configuring guardrails blind, unsure what type of protection should be strictly enforced, and what attack patterns to watch for.

Together, they move security from "list your AI" to "understand and control your AI."

The requirement to inventory AI applications is real and not going away. Compliance frameworks will continue demanding documentation, and governance teams will continue building registries.

But security teams need to push beyond the checkbox.

The question isn't "What models are we using?" The questions that matter are: What tools do they control? What data can they access? What instructions are they following? And what happens when those instructions come from an attacker?

Answering those questions requires depth. Deep repository scanning exposes the internals that inventory misses. Runtime guardrails enforce the policies that scanning reveals. And together, they transform AI security from a compliance exercise into an actual reduction of risk.

Your AI BOM satisfies the auditor. The map of capabilities, data flows, and supply chain risks satisfies the adversary's test.

Build the map.

Security teams ready to move beyond inventory should begin with their highest-risk AI applications: agents with tool access, customer-facing chatbots with data permissions, and any system where the lethal trifecta (private data, untrusted input, external communication) converges.

Scan the repositories. Identify the tools, the system prompts, the frameworks, and the supply chain artifacts. Map the blast radius before an attacker does.

Then instrument runtime. Deploy guardrails that enforce what scanning reveals. Monitor for the attack patterns that matter to your specific architecture.

The shift from inventory to insight isn't optional. As AI workloads move from passive chat interfaces to autonomous agents with backend access, the security community needs a more granular view of risk.

The AI BOM is a reasonable starting point. Deep scanning and runtime defense are where security actually lives.

Subscribe and get the latest security updates

Back to blog